Step by Step

A true story of grit, grace, and gratitude

Phnom Penh’s street vendors are among the various sub-cultures that give the hot, humid and crowded city its

joie de vivre. Some of the vendors set up small stands under shade trees along the sidewalks and provide a few plastic stools where their customers sit. Many of the vendors are young women and their stock-in-trade includes drinks and snacks, a pleasant smile and polite chit-chat. Their customers include school children, office workers, motorbike-taxi drivers, soldiers, and policemen. The atmosphere at these little stands is lighthearted and friendly. It’s a good job for a young woman. She has reasonable job security, low overhead, personal safety (being right on the street) and the opportunity to meet all sorts of people. Indeed, there is a good chance of striking up a friendship with a nice young man.

In 1991, Chea Sopheap, a pretty 21-year-old, was working at her small refreshment stand near the French embassy. While clearing some brush, she was suddenly thrown into the air by a deafening explosion. Unconscious and bleeding profusely, she was rushed to the emergency room at nearby Calmette Hospital.

Sopheap had stepped on a land mine. The blast blew off the lower part of her left leg.

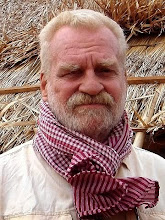

At that time, I was working with the Indochina Project of the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation. I was based in Washington, DC, where I read a news item about Sopheap’s injury. We had a physical rehabilitation center in Phnom Penh where we provided physical therapy and made wheelchairs and artificial limbs. Our program was run by my friend Ron Podlaski, a veteran of America’s war in Viet-Nam. I faxed Ron about Sopheap and was pleased to learn that he was already “on the case.” He had already been to the hospital to visit her family.

On Ron’s first few visits, Sopheap was still unconscious, but he met with her parents and told them he would see that Sopheap got the help and support she was going to need.

On his third or fourth visit, Ron found Sopheap conscious, but still in shock, unable to cope with what had happened to her and unable to imagine what her life would be like as a “cripple.” No more smiling and flirting with the young men who used to seek her out every day to banter with her over their sugarcane juice or coconut milk. Now she would be doomed for the rest of her life to sit on the ground in front of some dingy market or at the entrance to some dusty temple, begging for charity from strangers just to survive.

Ron, a straight-talking, hard-charging combat veteran tried to be encouraging, but his blunt bedside manner was a bit jarring. He told her the injury wasn’t so bad. ”It’s below the knee,” he said. “We can make you a new leg and have you up and walking as soon as your stump heals. You’ll be good as new and no one will even notice the leg. I’ll dance with you at your wedding.”

Sopheap burst into tears and screamed at him to go away. How could anyone be so cruel?

Ron went back to the rehab center and picked up a couple of men he wanted Sopheap to meet. The two hardened wheel-chair-bound land mine victims worked at the rehab center. Both had lost both legs above the knees and had gone through rehab and vocational training. He took them with him back to the hospital and watched as they wheeled themselves into Sopheap’s room. Ron said to Sopheap, “If you want to feel sorry for someone, feel sorry for these two clowns.” As Ron spoke, the two men were tipping their chairs back, balancing themselves on their rear wheels and giggling.

“Hey, sweetheart, don’t worry about it,” said the first one. “A simple wound like that . . . no problem. They’ll make you a new leg with a fancy rubber foot and nobody’ll know the difference.” The second guy chimed in, “You’ll still be able to wiggle your butt when you walk.” Ron punched them both playfully and said, “Hey, watch your language. You’re speaking to a lady.”

Sopheap feigned insult at the crude remarks, but there was just a slight loosening of the rigid lips and just the faintest whisper of her finely-crafted coquetry as she blushed and turned her head.

She was listening.

Sopheap had never really paid any attention to amputees before, though she saw them every day in the streets and parks and markets. She always thought of them as dirty and dangerous creatures to be avoided, and at first glance, her two visitors certainly fit the description. Still, they seemed cheerful, self-confident and she had to admire the way they had refused to be thrown away. These coarse and callous characters were survivors. Could she survive? How could she survive? Did she even

want to survive?

She was listening.

As she looked at them, her mind was doing its best to extinguish the tiny flicker of hope they had ignited. Guessing her thoughts — not difficult — one of them said, with a little twinkle in his eyes, “I stepped on that mine four years ago, two years ago I got married. We have one child and another on the way.” Sopheap did the math.

She was listening.

About a year later, I happened to be in Phnom Penh when Sopheap came into the rehab center to try out her new prosthetic leg (with the “fancy rubber foot”). Her stump had healed nicely, but of course it was tender and it would take a while for her to get used to supporting her weight on the strange new device.

The artificial leg had a nicely cushioned socket to snugly fit her stump. When she first stood on it, supporting herself by holding onto parallel bars on either side of an exercise walkway, her mother stood beside her and encouraged her. As she took those very tentative first steps, the pain was excruciating. I watched her face as the tears flowed. These were tears of physical pain combined with the frustration of failure. It was heartbreaking. It was completely beyond her imagination that she would ever be able to walk like this. She could just hobble around on crutches or use a wheel-chair. It seemed hopeless. For her, at that moment, it

was hopeless.

One of the rehab technicians assured her the pain would gradually go away as she grew accustomed to the new limb. “You’ll get used to it,” he said as he casually pulled up his trouser leg to reveal his own prosthesis. “We all do. You’ll love that rubber foot. It’ll flex and give you a little lift when you walk, jump or climb.” Walk, jump or climb? What was he talking about? She couldn’t even stand on her own. His amputation must have been different from hers.

Or . . . could it be true?

She was listening.

As she sat in the grass at the rehab center, her crutches beside her, Sopheap watched around her as people who had sustained dreadful injuries were riding bicycles, climbing trees and running around like “normal” people. In fact, as Sopheap came to understand, they were “normal” people. They were normal people who had survived terrible injuries. In fact, as she came to see, many people at the center were struggling with far more serious injuries than hers: above-the-knee amputations, multiple amputations, missing hands, blindness, disfiguring burns or scars and other traumatic injuries. Yet here they were: preparing meals, building wheelchairs, making artificial limbs, studying motorbike repair or lounging about in the shade playing with their spouses and children. A construction worker with no hands was shoveling gravel. A blind man was adjusting the spokes of a wheel to get the balance just right on a new wheelchair. Amputees with injuries like hers were playing table tennis, badminton, and jumping rope.

She was listening . . . and watching.

The next time I saw Sopheap was in 1994 after I moved to Cambodia. Ron had bought a pleasure boat to take tourists out on river cruises and had hired staff to serve drinks and snacks to the passengers. Sopheap was one of the waitresses. By then — a little more than a year after she got her new leg — she was so comfortable with it, concealed under her ankle-length sarong and stockinged feet, that the casual observer really would not have noticed anything unusual. True, she walked with a slight limp, but she walked with such pride and grace that it wasn’t significant. It was an amazing transformation in such a short time.

A few months later, Ron and I received invitations to Sopheap’s wedding. She was marrying a neighbor, one of the dashing young men who had admired her before her injury. He had visited her often in the hospital and had cheered her on during her two-and-a-half years of recovery and rehabilitation.

At the wedding reception, Ron and I were seated with some of Sopheap’s friends from the rehab center. Sopheap looked radiant in each of the several dresses Khmer brides wear during these highly choreographed celebrations. Just above each slippered foot, she was wearing a large traditional Khmer bangle at the ankle. It concealed the joint between the prosthetic leg and the “fancy rubber foot,” that was, indeed, giving her a natural little spring in her step as she moved about.

Finally, as the band started playing a slow number, Sopheap walked across the floor and stopped in front of Ron. Eyes glistening, palms raised together in the traditional gesture of respect, she smiled and said softly, “Shall we dance?”

-- Bill Herod